Event: Stellar-mass Black Holes

Date: First occurred ~13 billion years ago, continues today

“The space near a black hole is the most hostile environment we know of in nature.”

— Martin Rees

Dear Human,

Some stars die quietly.

Others end in fire.

And a rare few—so massive, so heavy, so hungry—they collapse not into silence, but into something stranger.

This is the birth of a black hole.

It begins like many stellar deaths: a giant star burns through its fuel, fusing lighter elements into heavier ones—until it reaches iron, the great cosmic dead-end. Iron cannot be fused to release energy; it only absorbs. With fusion halted, the outward pressure that held the star up vanishes.

Now, only gravity remains.

In most stars, gravity is balanced by pressure—heat, fusion, and the resistance of particles packed together. But in a collapsing giant, there is no more fuel, no more light, and no force strong enough to stop the fall. Even the repulsive strength between atomic nuclei—the strong nuclear force—is overwhelmed.

The star’s core begins to collapse inward. It falls so fast, and compresses so tightly, that no known force in the universe can resist it. The mass collapses to a single point of infinite density: the singularity.

And around it, space itself folds.

A black hole is not an object in the usual sense. It is a region—a distortion of space and time. Its outer edge is the event horizon—the boundary beyond which nothing can return. Not matter. Not light. Not even information.

To escape a black hole’s pull, you would need to move faster than the speed of light. But nothing in the universe can do that. Once something crosses the event horizon, it cannot send back signals. It cannot be retrieved. To the outside universe, it is erased—not by destruction, but by disconnection.

And yet, from a distance, it has a form.

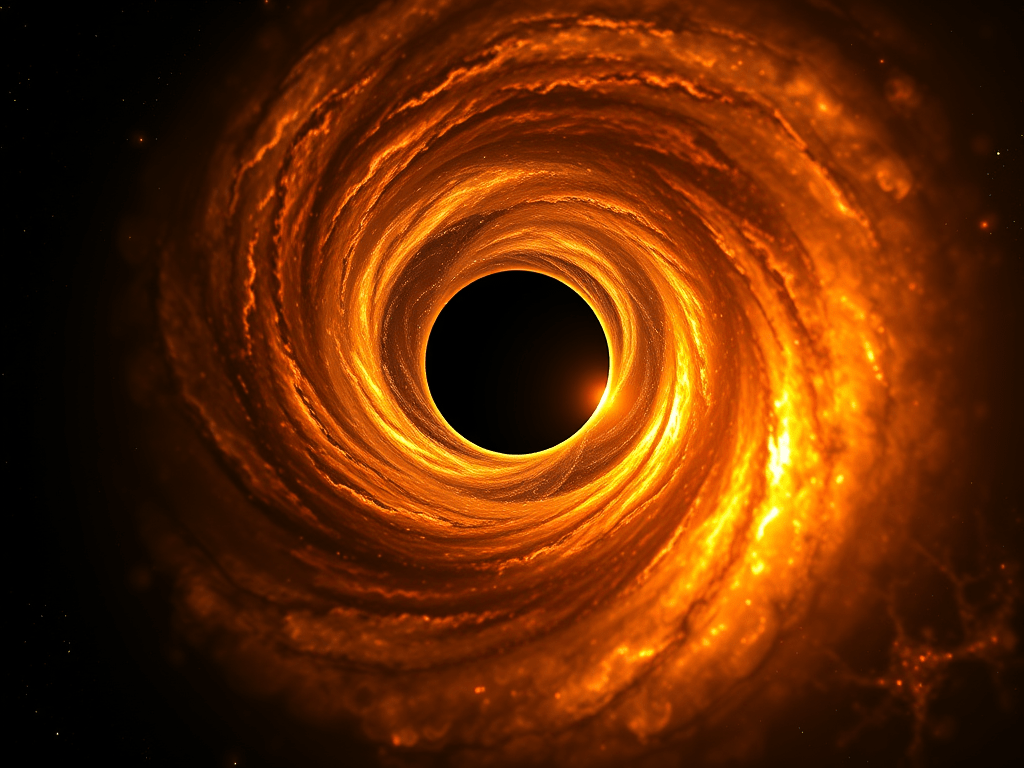

If you could see one, it would not be empty or invisible. A black hole surrounded by matter—dust, gas, a companion star—creates a spectacular display. The infalling material forms an accretion disk, a glowing halo of light and heat spinning near the speed of light. The closer matter gets, the hotter it burns. Near the event horizon, the disk shines in X-rays.

Surrounding the black hole is a region called the photon sphere, where gravity bends light into circles. You could see warped, twisted images of the universe—light looping back on itself, as if space were looking into a mirror.

As you approach, physics begins to break. Time slows down. For an outside observer, you would appear to freeze at the edge, fading into red. But from your perspective, you would fall quickly and without pause.

Crossing the event horizon is painless. There’s no wall. No signal. Just a line in space beyond which return is impossible.

Inside, the laws we know unravel.

In the smallest black holes, spaghettification awaits—your body stretched atom by atom, pulled apart by the brutal tidal forces of gravity. In larger black holes, you might fall without immediate harm—passing deep into the singularity, where space and time swap roles and all paths lead inward.

What happens next? No one knows. The math breaks. General relativity gives way to quantum confusion. No signals escape the event horizon—not light, not matter, not even the information we would need to understand what lies within. A black hole does not just hide its contents. It erases our ability to ask the right questions.

It is the most mysterious place in the universe—not just hidden from view, but hidden from knowing.

And perhaps that is the greatest truth a black hole holds:

Not that it destroys, but that it denies us the ability to understand.

The closer we get, the less we can know. Our light bends. Our time slows.

Even our information—the raw material of science—is lost beyond the horizon.

A black hole is not just a boundary of space. It is a boundary of understanding.

So we ask, and we wonder.

And maybe some paths will never be traveled—

not because the universe is unwilling,

but because it is built in such a way that some questions are meant to remain folded in shadow.

Pathfinder

Leave a comment