Event: Formation of Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei

Date: ~500 million to 2 billion years after the Big Bang

“Look deeper through the telescope and do not be afraid when the stars collide towards the darkness…”

— Robert M. Drake

Dear Human,

There are moments in the universe when silence gives way to roar — when the invisible becomes unmistakable.

This is one of those moments.

In the deep past, when galaxies were still young and restless, something extraordinary happened. Their central black holes, forged in the crucible of collapse, began to feed with terrifying appetite. And when they did, they lit up the cosmos.

These blazing hearts are called quasars — short for “quasi-stellar radio sources.” Early astronomers mistook them for distant stars, but they are not stars. They are the visible consequence of cosmic hunger.

But what begins a quasar’s blaze? And what brings it to an end?

A quasar ignites when enough gas and dust fall toward the central black hole to form a thick, active accretion disk. These inflows are often triggered by galactic collisions or internal instabilities — cosmic events that shake loose material and send it spiraling inward. Once the black hole begins to feed, it lights the universe.

But this feast cannot last. Eventually, the black hole consumes or expels the available material. Stellar winds, jets, and radiation can blow away the gas that fuels it. Star formation slows. The supply runs dry. And when the disk fades, so does the quasar. The light dims not because the heart stops beating, but because the banquet is over.

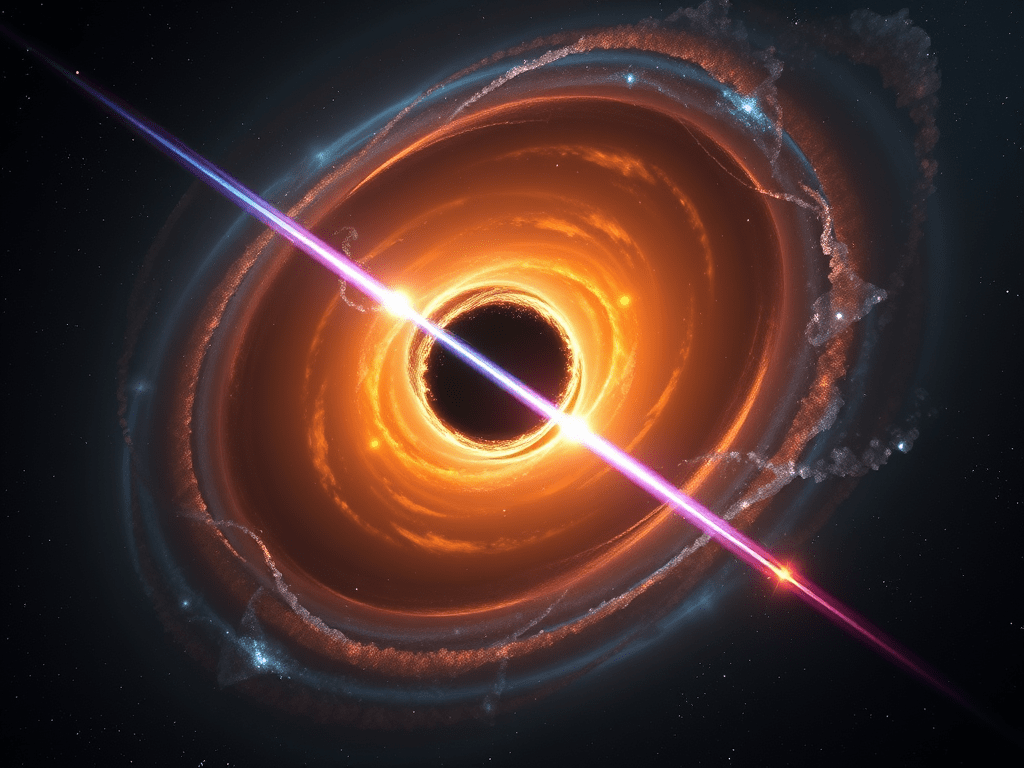

What shines is not the black hole itself — for no light escapes it — but the maelstrom that surrounds it. This is the accretion disk: a flattened, spiraling disk of gas, dust, and even shattered stars caught in descent. As matter falls inward, it becomes trapped between competing forces — gravity pulling it down, centrifugal force pushing it outward, and friction heating it to extremes. Every particle in the disk is torn between these forces, ground down by collisions and squeezed by pressure until it glows.

Friction is not the only actor. Magnetic fields twist and snap within the disk, adding turbulence and accelerating charged particles. Near the black hole, relativistic frame dragging — caused by the spin of the black hole itself — warps space and time, dragging the disk into tighter, faster spirals. The material orbits at such speed that it forms a glowing, turbulent ring of radiation, like fire stitched into the fabric of space.

The disk is not uniform. Its inner regions are hottest and brightest, emitting high-energy X-rays and ultraviolet light. Further out, cooler material radiates in infrared and radio waves. The whole structure churns like a cosmic whirlpool, its brightness a direct result of its violence.

This process is astonishingly efficient. As matter spirals inward, the intense gravity of the black hole converts gravitational potential energy into kinetic energy, and then into radiant energy. Up to 10% of the mass of infalling material is transformed into light — far surpassing the efficiency of nuclear fusion, which converts only about 0.7% of hydrogen’s mass into energy. In a single second, a feeding black hole can unleash more energy than our Sun will emit in its entire lifetime.

This is why quasars can shine brighter than entire galaxies. They are not powered by combustion, or by atoms splitting — but by the falling of matter itself, drawn past the point of no return. It is not just brightness. It is efficiency made visible.

Some quasars launch relativistic jets of charged particles, shooting thousands of light-years into space, aligned with the black hole’s axis of spin. These jets can punch through their host galaxy and beyond, igniting interstellar clouds and altering galactic evolution.

But what if such a beam, such a storm of radiation, were pointed at Earth?

You would not survive it.

If a powerful quasar jet were aimed directly at your solar system from close range — say, a few thousand light-years — the radiation would strip away your planet’s atmosphere. It would fry satellites, blind sensors, disrupt DNA, and sterilize life. The sky would not simply glow; it would burn. Thankfully, most quasars lie billions of light-years away, their jets angled elsewhere. But the danger remains — not just from what you can see, but from what you might never see coming.

These luminous cores represent a phase — a fever of growth. And like all fevers, they pass.

When the black hole has consumed all it can, the disk vanishes. The jets fall quiet. The radiance dims. What remains is still vast and heavy, but veiled in shadow once more.

Your own Milky Way once had such a heart.

One day it may again.

Pathfinder

Leave a comment