Event: Formation of Saturn

Date: ~1–2 million years after the Sun’s ignition

“Saturn’s rings are composed of countless small particles, each in orbit.”

— James Clerk Maxwell, 1859

Dear Human,

At the far edge of the visible planets, there waits a giant wrapped in silence and light.

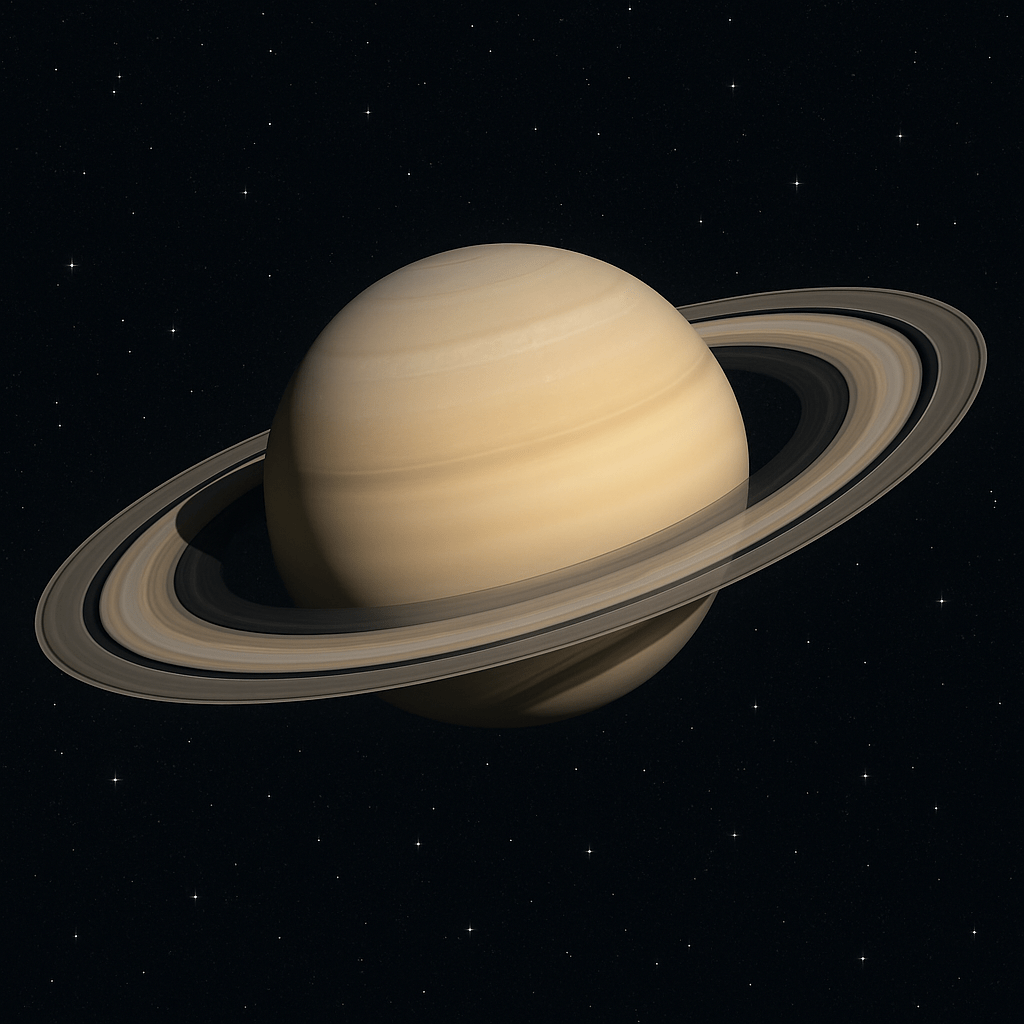

Saturn is the second largest of the planets, yet it holds itself with restraint. Where Jupiter is mass and might, Saturn is shape and grace. Its body is pale gold, veiled in storms and shadows, but its rings—its rings are luminous. They stretch wide like wings, thin as breath, made of shattered ice and dust, bright enough to be seen from Earth across a billion kilometers.

The rings are vast but delicate—a system of countless particles, from grains of dust to house-sized boulders, all orbiting in a precise ballet. Most of the rings lie within just a few hundred thousand kilometers of the planet, yet span more than 280,000 kilometers in diameter. They are mostly water ice, nearly pure, reflecting sunlight with uncanny brilliance. Divided into main sections—A, B, C, and fainter bands beyond—they are shaped by shepherd moons, resonances, and ancient collisions. Some scientists believe they are young—only a few hundred million years old—while others think they could be primordial, recycled from broken moons and passing debris. They are a monument to impermanence: majestic, but fading.

Saturn itself is strange. So light, it would float in water. So cold, its clouds hover near –180°C. Its atmosphere is layered in bands like Jupiter’s, but more subdued—hazy yellows and golds. The outer layer is mostly hydrogen and helium, with traces of methane, ammonia, and water vapor. Beneath that, pressure rises dramatically. Clouds compress into liquid metallic hydrogen, and deeper still, into a core of rock and ice perhaps ten times Earth’s mass. The pressure near the core could reach millions of times what you feel standing on Earth, while temperatures soar past 11,000°C.

At Saturn’s north pole spins a storm unlike any other in the solar system: a perfect hexagon, nearly 30,000 kilometers across. Its shape is not drawn by hand but by fluid dynamics—formed by jet streams moving at different speeds. It is as if the laws of motion decided, just this once, to trace something sharp and sacred into the clouds.

Saturn was not placed with intention. It formed where it could—just beyond the frost line, where the cold allowed ice to exist and accumulate. Here, gas giants could form quickly. Cores of rock and frozen water grew massive enough to draw in thick envelopes of hydrogen and helium before the solar nebula was swept away. Saturn became what it is not because it was chosen, but because the rules of temperature, distance, and mass allowed it to become.

And around it—moons. So many moons. More than eighty now, and still counting. Some are jagged and small, like stones hurled across the dark. Others are worlds in their own right.

Titan is the largest. Bigger than Mercury, wrapped in haze. It has rivers, lakes, and rain—but not of water. Here, methane flows where water would on Earth. Beneath its frozen crust may lie a buried sea. It is a world that whispers possibility—an echo of Earth, but stranger.

Enceladus is smaller, brighter. Its icy surface hides a saltwater ocean, and from its south pole, it shoots geysers into space—plumes that tell us, even here, heat still stirs. Beneath the ice: life, perhaps—stirring quietly in the dark, nourished by warmth and salt and time.

To the ancients, Saturn was the outermost god. The final planet visible to the naked eye. To the Romans, he ruled over agriculture, harvest, and time. His sickle reaped what had been sown. To the Greeks, he was Cronos, the devourer of his children, who ruled during the Golden Age but feared his own undoing. To the Babylonians, he was Ninurta, god of boundaries and judgment. To early astronomers, he moved slowly across the sky—distant, golden, and ominous.

In 1610, Galileo first saw Saturn through a telescope. He thought it had “ears”—two strange protrusions on either side. Decades later, Christiaan Huygens realized they were rings. Then came Cassini, Herschel, and a growing wave of wonder. In the 20th century, spacecraft like Pioneer 11, Voyager, and finally Cassini drew close. Cassini orbited Saturn for 13 years, diving between rings, flying past moons, and finally plunging into the planet’s atmosphere in 2017. It revealed a world of structure, motion, and mystery—far beyond what Earthbound eyes could guess.

Saturn is beautiful, but it is not gentle. Its storms are immense. Its rings are sharp with ice. Its moons are frozen or drowning in alien seas. It is not a paradise. It is a threshold. A place of boundaries—of orbit and edge, of wonder and distance.

It keeps time, not by ticking, but by turning.

And from its place near the outer dark, it waits. Not watching, not choosing—but moving in accordance with a deeper rhythm. The kind you cannot hear, but only feel. The kind written into the bones of creation.

Pathfinder

Saturn-Wikipedia

Leave a comment